Fashion Asia 2019: emerging Chinese designers (Jan 19)

Fashion Asia spotlights Chinese designers who have made the West sit up and take note. zaneta cheng meets three LVMH nominees and looks at how they’re proudly staking their claims on China’s new fashion frontier

Made in China” is undergoing a revolution, thanks in no small part to a group of independent Chinese designers who are working actively to change the loaded conno-tations those three words have carried in the past and, to a large extent, still carry today.

While China was associated with copycats and manufacturing for decades, the role the Chinese are playing in the global fashion market is evolving, from consumer to creator to buyer. Just a generation ago, designers of Asian descent – Alexander Wang, Phillip Lim, Jason Wu and Derek Lam, for example – took home fashion’s biggest awards, but aside from their names, their designs were bereft of cultural identity. Slowly, however, Chinese identity is being built on by designers such as Sandy Liang and Snow Xue Gao (see page 26), whose creativity celebrates their heritage not only through cultural symbols and motifs, but also more conceptual labels that are pushing fashion towards their own interpretation of the future.

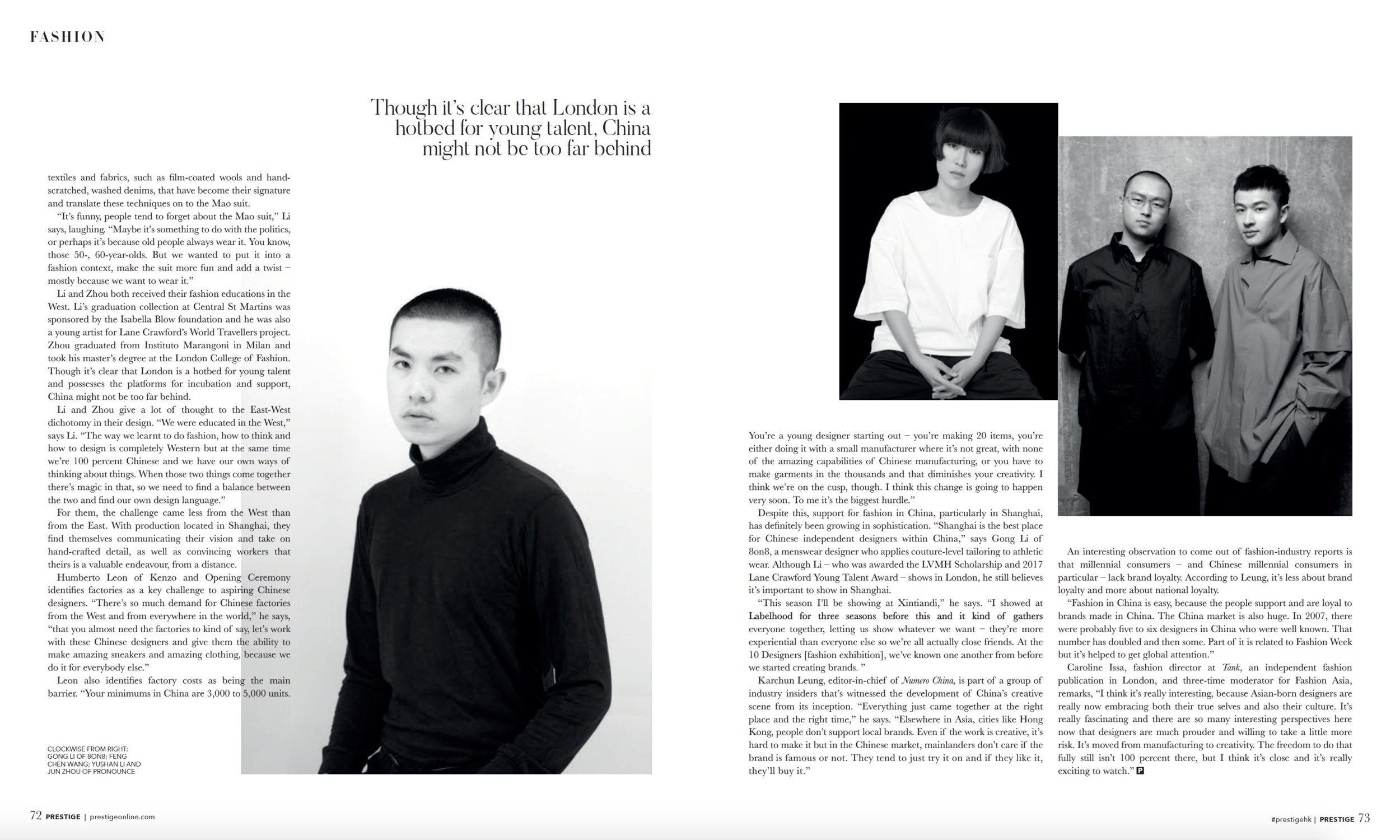

Feng Chen Wang doesn’t operate within what might be considered a traditional Chinese aesthetic. Armed with an MA from the Royal College of Art in London, a city where so many Chinese designers seem to be finding their footing, as well as an LVMH Prize nomination, she works with technical fabrics in large, seemingly utilitarian shapes that have seen her featured everywhere from Vogue to Business of Fashion to Hypebeast. Her first menswear show at New York Fashion Week led with her now-ubiquitous Made in China T-shirt.

Its success was unexpected, Wang says, given the mixed reactions when she first floated the idea. “A lot of people tried to stop me, because they were worried the press would focus on it in a negative way. But the result ended up being quite good, with people saying that we redefined ‘Made in China’. I don’t really want to broach this topic verbally, but if I show you my collection you can see – from quality to fabric to the way the pieces are styled – what Made in China means today. I want the detail of that craftsmanship, which is something I can’t explain, to say what Made in China of the future is.”

Although she got her start in London, Wang is looking to expand back home. Why? The answer is simple – “I’m based in the UK, but I want a second studio in Shanghai. I’m Chinese and the clothes will be 100 percent made in China. That’s in my blood.”

It’s a similar story for Yushan Li and Jun Zhou of Pronounce, a label based in Milan, where the two Chinese designers work to develop unique textiles and fabrics, such as film-coated wools and hand-scratched, washed denims, that have become their signature and translate these techniques on to the Mao suit.

“It’s funny, people tend to forget about the Mao suit,” Li says, laughing. “Maybe it’s something to do with the politics, or perhaps it’s because old people always wear it. You know, those 50-, 60-year-olds. But we wanted to put it into a fashion context, make the suit more fun and add a twist – mostly because we want to wear it.”

Li and Zhou both received their fashion educations in the West. Li’s graduation collection at Central St Martins was sponsored by the Isabella Blow foundation and he was also a young artist for Lane Crawford’s World Travellers project. Zhou graduated from Instituto Marangoni in Milan and took his master’s degree at the London College of Fashion. Though it’s clear that London is a hotbed for young talent and possesses the platforms for incubation and support, China might not be too far behind.

Li and Zhou give a lot of thought to the East-West dichotomy in their design. “We were educated in the West,” says Li. “The way we learnt to do fashion, how to think and how to design is completely Western but at the same time we’re 100 percent Chinese and we have our own ways of thinking about things. When those two things come together there’s magic in that, so we need to find a balance between the two and find our own design language.”

For them, the challenge came less from the West than from the East. With production located in Shanghai, they find themselves communicating their vision and take on hand-crafted detail, as well as convincing workers that theirs is a valuable endeavour, from a distance.

Humberto Leon of Kenzo and Opening Ceremony identifies factories as a key challenge to aspiring Chinese designers. “There’s so much demand for Chinese factories from the West and from everywhere in the world,” he says, “that you almost need the factories to kind of say, let’s work with these Chinese designers and give them the ability to make amazing sneakers and amazing clothing, because we do it for everybody else.”

Leon also identifies factory costs as being the main barrier. “Your minimums in China are 3,000 to 5,000 units. You’re a young designer starting out – you’re making 20 items, you’re either doing it with a small manufacturer where it’s not great, with none of the amazing capabilities of Chinese manufacturing, or you have to make garments in the thousands and that diminishes your creativity. I think we’re on the cusp, though. I think this change is going to happen very soon. To me it’s the biggest hurdle.”

Despite this, support for fashion in China, particularly in Shanghai, has definitely been growing in sophistication. “Shanghai is the best place for Chinese independent designers within China,” says Gong Li of 8on8, a menswear designer who applies couture-level tailoring to athletic wear. Although Li – who was awarded the LVMH Scholarship and 2017 Lane Crawford Young Talent Award – shows in London, he still believes it’s important to show in Shanghai.

“This season I’ll be showing at Xintiandi,” he says. “I showed at Labelhood for three seasons before this and it kind of gathers

everyone together, letting us show whatever we want – they’re more experiential than everyone else so we’re all actually close friends. At the 10 Designers [fashion exhibition], we’ve known one another from before we started creating brands. ”

Karchun Leung, editor-in-chief of Numero China, is part of a group of industry insiders that’s witnessed the development of China’s creative scene from its inception. “Everything just came together at the right place and the right time,” he says. “Elsewhere in Asia, cities like Hong Kong, people don’t support local brands. Even if the work is creative, it’s hard to make it but in the Chinese market, mainlanders don’t care if the brand is famous or not. They tend to just try it on and if they like it, they’ll buy it.”

An interesting observation to come out of fashion-industry reports is that millennial consumers – and Chinese millennial consumers in particular – lack brand loyalty. According to Leung, it’s less about brand loyalty and more about national loyalty.

“Fashion in China is easy, because the people support and are loyal to brands made in China. The China market is also huge. In 2007, there were probably five to six designers in China who were well known. That number has doubled and then some. Part of it is related to Fashion Week but it’s helped to get global attention.”

Caroline Issa, fashion director at Tank, an independent fashion publication in London, and three-time moderator for Fashion Asia, remarks, “I think it’s really interesting, because Asian-born designers are really now embracing both their true selves and also their culture. It’s really fascinating and there are so many interesting perspectives here now that designers are much prouder and willing to take a little more risk. It’s moved from manufacturing to creativity. The freedom to do that fully still isn’t 100 percent there, but I think it’s close and it’s really exciting to watch.”